A Universal Theory of Change

Is excessive rational scepticism of ancient wisdom getting in the way of more radical forms of meaning-making?

🎼 While My Guitar Gently Weeps by Black Chamber

“The entire evolution of science would suggest that the best grammar for thinking about the world is that of change, not of permanence. Not of being, but of becoming.” — Carlo Rovelli

As varying archetypes of the ‘Change Maker’, systems thinkers, futurists and designers all share one thing in common: the need to encode our complex, shapeshifting reality to some small degree. Not just to capture the nature of things for its own sake, but an attempt to make sense of such complexity, and then harness the wisdom provided to enact positive change in the world. To hopefully trigger inspiration and imagination for a brighter future tomorrow. For a designer, it may look like Gestalt principles or cognitive biases. To a foresight futurist, a megatrends catalogue. Systems thinkers draft ecosystem or causal maps to better determine the relationality of actors in poorly understood terrains. All such techniques seek to know the world in some small way, and to use this knowledge to ensure action takes a desired effect.

So it stands that our disparate Theories of Change, no matter how grandiose or varied, can ultimately be boiled down to expressions of pattern recognition of the causality and consequences of behaviour over time: When that occurs, this happens. At least in theory, based on repeated prior observation or experience. It’s then a case of knowing how, when and where to intervene to shape more desirable destinies.

In many ways, this cognitive technology of sensemaking — spotting recurring causation over time and turning it into digestible heuristics of varying fidelity — is an intrinsic part of the fabric of our daily reality. Or at the very least, how we deal with reality as human beings. To spot these consistencies is to see the repeating remixes of reality play out over time. The asymmetrical arrow of time is therefore more often felt, through our lived experience, as a rhyming loop of time; a cyclical flux more than a linear progression. After all, we live with the seemingly oxymoronic contradiction that while the only constant may indeed be change, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

An essential aspect of wisdom, perhaps at its very core, is this ability to know how best to anticipate and act on the insight of pattern recognition. To avoid, create, or improve contextual repetition in the world. To (re)make or break new patterns of being. To change how things change.

Why is this relevant? Well, imagine for a second, attempting not merely to codify common psychological ‘tricks’ of visual perception (i.e. Gestalt), or subjective judgement (i.e. cognitive bias), or the prevalence and influence of shared global events (i.e. megatrends), or the causes and effects within a bounded sphere of control (i.e. system maps), as designers, futurists and systems thinkers find necessary.

Imagine attempting to codify the nature of change itself: What do its patterns look like? And how do we respond appropriately to them?

And not just to encode them at a single resolution, but to do so at various scales; from a set of irreducible ‘atomic’ forces, through their combination into ‘raw’ elements, to their ‘entangled’ manifestations in our interactions with the wider world at large, from the micro all the way up to the macro.

Perhaps this degree of exhaustive documentation is better suited to the preserve of science alone. I’m reminded in particular of the counterintuitive and irreconcilably paradoxical conundrums that continue to emerge from the dizzying migraines of quantum physics. The need to get the story straight with absolute precision (and the headaches that creates in itself).

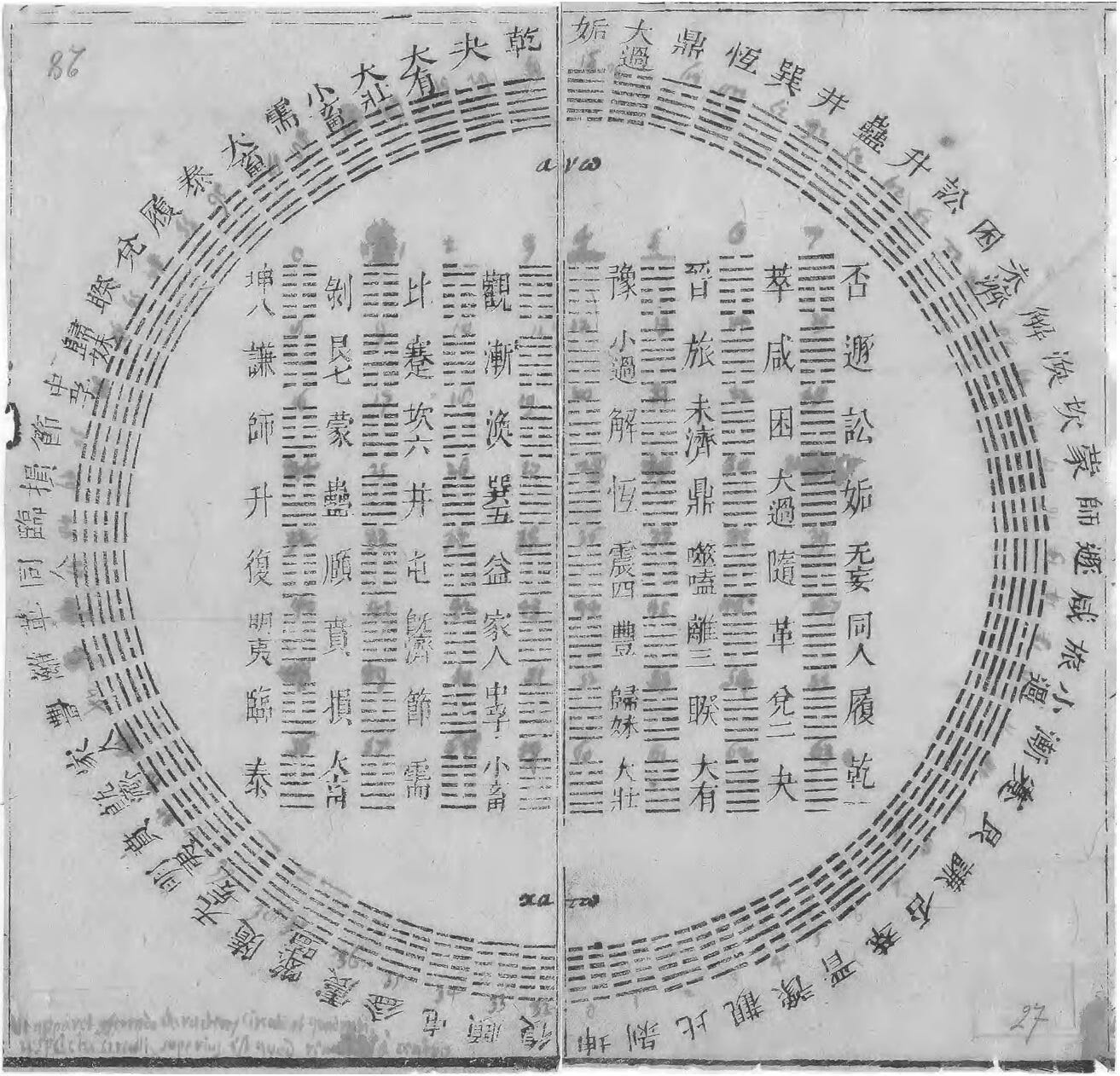

But the lofty ambition for a multi-tiered pattern library of change has nonetheless been the legacy of the mighty I Ching, or Book of Changes — a foundational tenet to the Chinese cosmological philosophy behind both Confucius and Taoism, as well as Carl Jung and the Western counter-culture movement of the 1960s and beyond. Undoubtedly it is an imperfect and imprecise approximation of the finer-tuned nature of the flux of reality, as are all such heuristics, but one that has roughly 3000 years of precedent and profundity possibly worth paying attention to.

Turn and face the strange

The I Ching is an ancient, quasi-mythical text, of unknown authorship, which is beyond comfortable comparison to anything else in existence today. It bears no parallel for instance with the Christian or Hebrew Bible or the Muslim Quran, as its sole function was believed to be as a divinatory means to enquire into the suitability of a proposed course of action.

In reductively simplistic terms, its content is divided into 64 sections, each of which corresponds to a specific pattern of change, inspired by the interactions of nature.

Random numbers were used to determine a relevant section of content most appropriate to the situation at hand, and, as was likely typical of the time, this randomness was construed as divine intent (otherwise known as cleromancy). As you can probably imagine, given the timespan since its authorship, its content is not always straightforward to understand. Often enigmatic and cryptic, interpretations are still very much alive by Sinologists, scholars and translators to this day, as evidenced by some of the following, albeit selective and abbreviated, extracts below (by Wen, 2023):

䷩42: Burgeoning (益)

When sages see the good of others, they are inspired to be better; and when they see the fault of others, they correct that fault in themselves. Auspicious to cross the great stream. (Line 1) There is no blame.

䷙26: Cultivate the Supreme(大畜)

Study the words and deeds of the great and wise before you; that way you can build and develop your virtue. Do not eat meals from home. (Line 2) An axle from the carriage is broken.

䷼ 61: Faith Within (中孚)

A wind blows across the lake: gentle thoughts nourish and bring joy. The sage deliberates on the transgressions of humankind but delays executions. Persuading a piglet and fish: good fortune and prosperity arrive for you. Favours granted. Auspicious to cross the great stream. (Line 2) A crane is crooning in the shade. Its chicks answer the call. I am with you, diffused everywhere.

The I Ching gained cult popularity and rose to a degree of prominence in the West as part of the counter-culture of the 1960s. It inspired the song title of The Beatles’ While My Guitar Gently Weeps, the lyrics of Joni Mitchell’s Amelia, and Philip K Dick’s story arc for The Man in the High Castle, while Leonard Cohen and Bob Dylan, amongst others, were known fans. Dick later became such an addict it triggered his paranoia in believing it was in fact a “malicious spirit” to be avoided. The propensity for his consumption of psychedelics probably shouldn’t go unmentioned here.

“If time is fractal, then implicit in that statement is the idea that patterns repeat on many many levels. Well that is really what all systems of divination all over the world have always claimed. That… somehow, these objects, these processes, become microcosms of the larger situation in the macrocosm.” — Terence McKenna

Unsurprising then that the mythic ethnobotanical philosopher Terence McKenna, author of the Stoned Ape theory of human evolution, also fell under its sway. He undertook a mathematical analysis of the numerical sequencing in the I Ching to arrive at a theory — conceived after Amazonian experiences with psilocybin mushrooms of course — that supposedly demonstrated the ebb and flow of novelty in the universe. Such novelty, or its opposite, habit, had a fractal patterning over time, with each successive cycle trending towards increased novelty, and therefore complexity. Peak novelty, according to his prediction engine ‘Timewave Zero’, would be reached around the end of 2012 (coincidentally also the predicted Mayan calendar cataclysm), at which point a singularity of infinite complexity would occur. Sadly he died in 2000 so didn’t get to witness it himself. While I struggle to remember precisely what I was up to at the time I’m fairly sure I’d have recalled the moment were it anything close to his hypothesis:

“The universe disappears, and what is left is the tightly bound plenum, the monad, able to express itself for itself, rather than only able to cast a shadow into physis as its reflection…It will be the entry of our species into ‘hyperspace’, accompanied by the release of the mind into the imagination.” — Terence McKenna

Non-causal entanglements

As insanely fascinating as this heritage is, for clarity, I’m not here to evangelise any alleged spiritual or transcendent dimensions of the I Ching, especially given how reticent and non-commital I am of “going there”, so to speak. Nor am I necessarily intrigued by how it gets used or interpreted by others. When I first discovered and delved deeper into its lore what stood out to me was its affinity with, and sometimes significant preemption of, subsequent concepts in a variety of fields spanning across both the humanities and sciences; from the aforementioned theories of change, and the ambitious notion of a pattern library of change ‘to rule them all’, to as extreme a contrast as binary computer programming and even quantum physics — domains rich in rational scepticism of anything that can’t be demonstrably and often quantifiably proven.

Niels Bohr, the celebrated Nobel Prize-winning physicist, also became intruiged by East Asian philosophy and its sometimes pseudo-spooky logic. He even referenced the I Ching and yin-yang to communicate his seminal quantum theory, the Principle of Complementarity, whereby the behaviour of objects are interconnected with the instrument that observes them, in a way beyond obvious notions of causality. i.e. Sometimes things that don’t appear to be related, are.

Interestingly, a similar concept refracts and echoes within Carl Jung’s psychological theory of Synchronicity, whereby the behaviour of events are interconnected with the mind that observes them, in a way beyond obvious notions of causality. i.e. We sometimes apply meaning to events that don’t appear to be related. Or: sometimes things that don’t appear to be related, are.

Unsurprisingly, Jung was exposed to the I Ching prior to the formation of his theory, as well as the influences of preceding German philosophers, Leibniz and Schopenhauer. He was a strong advocate of it, recommending readings to his patients as a method for insight into their inner states. He later worked on a dual-aspect theory for “a psychophysically neutral reality”, or Unus Mundus, alongside, surprise surprise, another quantum physicist Wolfgang Pauli.

The speculative diviner

Which brings me to my most prevalent interest in the I Ching. There exists something way beyond the readings themselves, which are, after all, texts written from an entirely abstract era of legend relative to our vantage point, high up the crumbling edifice of modernity. However, as quantum physics shows us, modernity doesn’t always guarantee the certainty of irrefutable answers. The more we may decipher the absolute here or now, the more we may also obfuscate the then or there. What ultimately maintains my fascination with the I Ching is its ability to generate efficacy irrespective of the absolute or relative precision of its accuracy.

So if this book of changes does indeed offer something more meaningful than merely a historical curio, it is foremost as its role as a singularly distinct and unique synchronicity machine; providing symbolic, non-causal relationships between the present moment, our psychological state, and the encoded patterns of change observed in — and inspired by — nature roughly three millennia ago. Of purposefully suggestive coincidences and connections between events we experience in the world, our contemporary minds, and the wisdom of ancient philosophers. Combined with its deeply ritualistic and thoughtful mechanics, it helps provide the possibility to find meaning in a way that brings sharper clarity to the present and breathes agency into the creation of possible futures. At the very least, perhaps at its very core, in the most atomic sense, a randomisation game engine to break the default patterns of dull predictability and repetitious habit.

Author Will Buckingham sums this up perfectly when he describes the I Ching as a provider of “better uncertainties”, rather than necessarily the superstitious magic of prediction:

“It integrates the fact of unknowing into the fabric of my thinking, opening me up to hitherto unimagined possibilities. Scattering the monotony of my either/or dilemmas into a myriad of forking paths.”

If it wasn’t already obvious, I’d like to make the case, to even the most ardent (ir)rational sceptic of anything even remotely unverifiable, that this seemingly occult and esoteric codex from the distant past is perhaps not quite so different, or even outrageously inaccurate or unhelpful (as some of us would like to believe), from the rules, principles, catalogues, maps and games we use today in our daily roles as innovators, systems thinkers, futurists, designers, or the multitude of various flavours of changemaker: To make sense of complexity, however imprecisely, and then harness the wisdom provided to enact positive change in the world. To hopefully trigger inspiration and imagination for a brighter future tomorrow.

䷕ 22: Luminosity (賁)

There is fire at the base of the mountain. The adornments bring favour.

If this article perked your curiosity into the I Ching, please consider supporting Better Uncertainties: An oracle card deck for changemakers, only available on Kickstarter throughout January 2024.

Excellent article, Andy. Although perhaps not a direct response per se, some of this made me feel the relevance of the UTOK (universal theory of knowledge) work Vervaeke and Henriques cover in this series: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLTJe1xFfoxrAIyl5r1dB4La6zzMfUZVyd